- Home

- Jeff Dawson

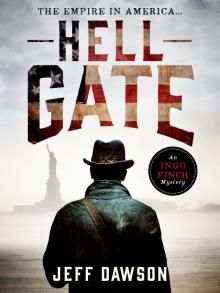

Hell Gate

Hell Gate Read online

Hell Gate

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Based on historical events

PART ONE

Chapter 1 East River, New York City – June 17th, 1904

Chapter 2 Nine months later

Chapter 3

Chapter 4 The North Atlantic – two days before disembarking

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

PART TWO

Chapter 21 Hell’s Kitchen

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29 Washington DC

The Waldorf Hotel, New York

About the Author

Also by Jeff Dawson

Copyright

Cover

Table of Contents

Start of Content

To my family, as always

Three may keep a secret if two of them are dead.

Benjamin Franklin

Based on historical events

PART ONE

Chapter 1

East River, New York City – June 17th, 1904

The body bobbed on the spring tide.

‘The oar, use the oar.’

‘Boat hook’s fine,’ muttered the constable.

‘The oar,’ urged the harbourmaster. ‘Some goddamn respect!’

He nudged the tiller and rubbed his eye. Two days on and the smoke was still curling, funnelled down the channel between Manhattan and Queensborough. Acrid, stinging, it rose thick to screen the noonday sun.

The constable shrugged and shouted forward.

‘You heard what he said. Use the oar.’

‘He has a name – Tobias.’

Pressing a kerchief to his mouth, the constable edged towards him, careful not to tread on the rowing boat’s grim cargo.

Tobias rolled his eyes. He lay prone at the bow and reached out, smacking the blade down hard.

‘Again…’ barked the constable. ‘Too far to the right.’

Gentle waves lapped the hull. A bell clanged on a buoy. Somewhere in the distance a foghorn droned, sound muffled by the smog. Ahead, in the Hell Gate strait, the waters swirled white. They could not afford to drift.

The oar went closer and flicked the leg.

‘Couple of inches… There!’

The white pinafore dress billowed like the dome of a jellyfish.

‘Female… juvenile…’ muttered the constable.

‘Some compassion,’ scolded the harbourmaster. ‘It’s a little girl.’

He gave himself a moment.

‘What d’ya think? Nine years old… ten?’

The constable shrugged again.

‘Okay,’ said the harbourmaster and nodded to the shore.

The constable waved landward, signalling no room for any more. He was not sure if they could see him through the smoke.

From the plane trees that lined the river path, before the grand timbers of the Gracie Mansion, the man with the grey silk suit discerned the rowing boat turn.

‘How many?’ he asked.

His colleague scanned with binoculars.

‘The negro fellow just pulled out another. Small. A child. That’s five, I think.’

Most of the bodies had washed up round the bend, on the rocks of the Brothers Islands, but some were still drifting down.

‘I mean, how many in total?’

‘Twelve… fifteen hundred…?’

The man in the suit exhaled a whistle. Ash was still falling and he brushed it from his shoulder. He nodded back up to the sidewalk where his valet stood by the idling red Ford – dutiful, alert.

A slender man of near seven feet tall, he had the pockmarked skin and high cheekbones of his First Nation forebears. His black hair was worn symbolically long – bunched and beaded. He stooped to open the door.

Back at the low-tide mark, desperate men waded to their chests. They hauled the boat onto the shingle. Tenderly the bodies were laid next to the others, a row that already stretched ten yards.

Policemen logged the details. Someone from the coroner’s office set up a camera. One angry man threatened to wrap the tripod round the photographer’s head. Women dressed in black sniffled quietly.

In the June heat, the scent of death oozed along the waterways. No posy of flowers – and there were many strewn – could mask the stench. At the recognition of her child, a mother’s legs buckled and she released an animal moan. Others rushed to support her.

In the distance, the huge pleasure steamer lay part submerged, like a fat man wallowing in a bathtub. Pitched to one side, a giant paddle had lifted near clear of the water. From the portholes the black cloud billowed, the heat still too intense for the Fire Department tenders.

* * *

After dark, the orange glow from the Arlington Hall windows drew the public. In the warm night air they came, black-clad, ambling across Tompkins Square Park – ‘Der Weisse Garten’ as everyone still called it – the Schwartzmeiers and the Lindemanns; the Goehles and the Steins; the Lüchows, the Geigers, the Allings; all greeted with lingering, cupped handshakes and consoling hugs.

Some arrived in buggies, clopping across the cobbles of St Mark’s Place. Others trudged out of the Atlantic Garden Bierhaus – sorrows drowned like their loved ones – while the ‘El’ trains clattered on the tracks above the Bowery.

Inside, the tension was palpable, the hall packed – men standing, lining the walls beneath the black crêpe frieze, while their womenfolk squeezed in to take the seats. As the speakers began, a crush swelled around the doorway, latecomers unwilling to divert from the tide of emotion that poured with every oration.

The pastor spoke first, his face lined, drained. Up on the stage he looked lost, a ghost behind the lectern. It was members of his own congregation – the St Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church – who had chartered the pleasure steamer for the annual day out, he explained. It had been a regular treat for the families, the seventeenth such excursion, heading for a picnic at Locust Grove off Long Island Sound.

Wisely eschewing his profession’s convention that God’s will might have been responsible for the boat then catching fire and sinking, he gave a meditation on grief. He could still not believe it: that it could happen to his own flock… that tomorrow alone would see a cortege of two hundred hearses…

Then he sat back down, broken.

The President of the District Bund went next, with far less room for tolerance. Not three hours ago, he told them, he had received information from a reporter on the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung who had been scouring the city archives. He waved a sheaf of papers for effect.

The steamer, the General Slocum, had had its career as a pleasure boat punctuated with accidents, he revealed – beached twice off Rockaway; again at Coney Island; collisions in the East River and off Battery Park – mishaps that had been hushed up by the Port Authority.

A murmur swept the room.

The boat, grossly overcrowded, was a death trap – straw and oily rags left lying around; storage areas full of gasoline; a lamp that was knocked over; a captain who ignored word of a blaze. A 12-year-old boy – a 12-year-old boy! – had been left to raise the alarm.

The chorus of disapproval swelled.

The General Slocum’s crew had never c

onducted a fire drill, for heaven’s sake. Not once. The lifeboats were wired to their housings. The fire hoses were rotten and had crumbled to dust. Mothers placed children in life preservers and threw them into the water only to find they had been padded with iron bars – iron! – to cheat on the inspector’s weight specifications.

His voice began to crack.

‘The children. The children…’

Someone came to ease him from the lectern, prising away his fingers.

‘Thirteen hundred. Thirteen hundred,’ he wailed. ‘Burnt, drowned, all gone. Our people, our community… Gone!’

The room hummed, buzzed. Grief had turned to anger – a force, the next speaker knew, that could be harnessed, captured, utilized.

A community elder held two palms aloft, an appeal for calm, before his sombre introduction to a special guest, a man who had dropped everything to rush here from Ohio. ‘Head of the American National Party – some say the next resident of the White House – Senator Abel Schultz.’

Polite applause rattled in expectation.

If there was one thing clear it was that Senator Schultz knew how to work a room. He entered at the back, such that news of his advent rippled forward, adding a choreographed sense of theatre as heads spun this way and that.

He was a man of modest height, around 50 years old, with craggy features and piercing blue eyes, oiled hair only slightly greying. He took his time, moving down the aisle, clutching hands, laying palms.

As he mounted the steps, slowly, deliberately, a spotlight fizzed into life. It cut through the fug of tobacco smoke to cast the Senator in a pool of light, throwing his silhouette onto the velvet curtain behind. The pastor blinked in the glare. The President of the Bund hoisted his papers to shield his eyes.

‘Ladies and gentlemen, Damen und Herren,’ Senator Schultz commenced. ‘I have the dubious distinction of having grown up during the Civil War, the greatest tragedy ever to have befallen our great nation.’

He took his time, his tone flint-sharp, piercing… stabbing out every syllable, his enunciation crystal clear.

‘But in the 40 years that have ensued, a time of peace and prosperity, not one calamity – the Great Chicago Fire… the Galveston Hurricane… or the Johnstown Flood – has touched me, touched this community, in the way that this… this damnation on the East River that has come to pass.’

There were shouts of ‘Amen’, shouts of ‘Ja’.

‘But, my friends, do you know what is just as tragic? It’s that not two days into this abomination – two days – while bodies are still being identified in the morgue on the Charities Pier, heartless landlords have already begun exploiting this community’s loss to further their own ends, seizing property, raising rents. I say shame on them. SHAME!’

He leaned forward.

‘Here in Manhattan, Little Germany, our own dear Kleindeutschland, was already being squeezed by the Italians, the Irish, the Chinese and the Russians. Alas, this… this “Slocum Disaster”, marks the day that our walls were breached…’

He hung his head, shaking it in disbelief.

‘…breached terminally.’

A smattering of handclaps followed. A recognition. There were words exchanged between neighbours. Schultz had tapped into something.

‘A curious thing. But for one vote in Congress in 1776, the language of our United States would have been German, not English. Did you know that?’

Some nodded, some shook.

‘Did you know, too, my friends, that, after Berlin and Vienna, New York is the third-largest German city on God’s earth? The third largest.’

He quickened the pace and scanned the room.

‘Not coolies or navvies. Not scroungers or drunks. No. No! Just humble, honest, hard-working folk who settled here in pursuit of a better life… a dream.’

He waved a hand towards them.

‘Tradespeople, family people…’

The hand picked out faces at random, as if he knew them personally.

‘…engineers, architects, machinists, boilermakers, road-builders, teachers, tailors, bakers, shoemakers, dressmakers…’

The applause came back stronger.

‘Fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers…’

He thrust his index finger skyward, as if channelling a higher power.

‘The founders, the forgers of this young nation. Model Americans.’

He nodded theatrically at his own truth, puffing out his chest, looping thumbs into lapels. He left the sanctity of the lectern, pacing, turning on cue as the rehearsed thoughts struck him.

‘Oh yes. Right across the land, my friends. In New York City as it is in the mighty Steel Belt which stretches clear through the Middle West – in Pittsburgh, in Scranton; in Cleveland, in Toledo; in Fort Wayne, in Chicago, in Milwaukee – where the hands and brains of three million German-born sons, German-born daughters, stoke the industry, the engine, which drives America…’

He quickened the pace.

‘…a land whose very liberty was preserved by the bravery and courage of German–American soldiers – men who fought for the Union Army in that great and terrible war of which I just spoke – 200,000 warriors…’

The clapping grew furious, rapid.

‘…heroes of the 9th Ohio, the 74th Pennsylvania, the 9th Wisconsin… and, of course, the 52nd New York!’

An old man with a chest full of campaign medals rose to his feet, tears streaming down his cheeks. There were shouts of encouragement. Schultz was working up a head of steam, forgoing his soliloquy to bark his sentences in stentorian tones.

‘And what thanks do we get? Not that we ever asked for any… None.’

His face was a nickelodeon star’s rictus of exaggerated disgust.

‘NONE!’

He slammed his hand down hard on the lectern’s wood.

‘Our Volk are being demonized. Hell, and if you’ll forgive such a word, Pastor…’

He turned for effect. The pastor nodded his pardon. There was a release of guilty laughter.

‘…even Anglicizing their names – Schmidt to Smith, Braun to Brown – ashamed of their heritage! Ashamed of our Old Country. That one across the water…’

He pointed to the distance. It might as well have been to somewhere across the street.

‘…ashamed because the US Government, be it Republican or Democrat, has no time for people of German stock, wherever they may be.’

The nodding continued.

‘Too busy sucking up to Great Britain,’ he mused, before shifting again to the shake of incredulity. ‘Whose yoke crushed this land till we threw it off in pursuit of our own manifest destiny.’

He threw his palms up in utter disbelief.

‘And to the decadent French…’

He nearly spat the word out.

‘And the casualties in all this? People like you. The people grieving in this very room.’

The jerk of his head made his hair flop forward. He smoothed it back.

‘The same people who will, sure as damnit, have to suffer in silence through any so-called “inquiry” into this travesty, be it State or Federal, while the perpetrators of this crime, aided and abetted, wriggle themselves off the hook with a litany of cockamamie excuses.’

He took his time.

‘But we say “No”!’

He waved both fists in the air, roaring for all he was worth.

‘NO!’

He stood still now, waiting for calm, waiting for the punch.

‘I want to remind those men in New York City Hall…’

The pointing resumed.

‘…those men in Washington, of words decreed by another, a man far wiser than I…’

He issued a smile of self-deprecation, his head bowed, humble.

‘…that all men are created equal.’

There came further murmuring, nods of approval. He tripped round the acclaim with staccato jabs, finding gaps to punctuate the applause.

‘We Germans will not be bowed. We will

fight back! And seeking justice for this catastrophe, this slaughter, this massacre aboard the accursed General Slocum… This will be our beginning!’

He was straining to be heard now, just the way he wanted it.

‘Your loved ones. Our loved ones. As God is my witness, I make a solemn promise to you this day. WE WILL NOT LET THEM DIE IN VAIN!’

The room was on its feet – every last person cheering, hollering, exhorting.

At the side of the stage, the man in the expensive grey suit nodded discreetly at the triumphant Senator, arms thrown wide, basking in his glory. With his angular Amerindian accomplice in tow, he slipped out through the stage door into the night.

Chapter 2

Nine months later

Ingo Finch leaned on the rail and pinged the stub of a Navy Cut out into the breeze. From up high on deck he watched it dance downwards, not sure if it ever hit the water.

He gazed up again.

‘I didn’t know she was going to be blue.’

‘I’d say more green,’ replied the gent next to him.

‘In all the pictures, the illustrations, she’s a copper colour.’

The man, a New Yorker, smiled.

‘When the French gave it to us – a gift – it was just that, copper… literally made of copper. But the air, it oxidises, creates a coating… a patina.’

He dragged on his cigarette and spluttered a bit.

‘They were gonna paint the thing, restore it to the original colour, but folks kinda got to likin’ the lady the way she is.’

‘Blue,’ teased Finch.

‘Bluey green, I’ll give you that,’ the man chuckled. ‘One thing’s for sure, you can’t miss her.’

He coughed again, harsh.

‘Holy Moly, your English smokes!’

The Statue of Liberty continued to slide past on the port side, staring her dull-eyed stare, waving her golden torch to all incomers – ‘your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free’ as the inscription put it – most of whom, observed Finch, seemed to be straggled in miserable-looking queues on Ellis Island just behind her.

Hell Gate

Hell Gate